The utilization of music as a way to connect with a constituency and spread information throughout the masses has long since been a practice across many spheres of influence. From religious institutions to political parties, the ability of music to become deeply ingrained in culture has been an ideal quality that many leaders have attempted to harness and further their cause. In East Germany, the Sozialistische Einheitspartei Deutschlands, or SED, saw an opportunity to create art programs that were entirely overseen by the government in their attempt to bring Marxist ideology and a new East German identity to the forefront of common discourse. As the scholar Elaine Kelly notes, “…the history of music and socialism is one that enacts moments of political hope. It is also one, however, that reveals the disjunctions between ideals and practice that frequently beset utopian socialist projects”. By disseminating socialist content through a musical platform, the audience became more capable of interacting with the political circle and engaging in the creation of original art. Music is not only an ideal mechanism to influence the communities in which it circulates, but it can also show a disparity between the goals of an institution and the desires of the people. Consequently, this essay will explore how different facets of political pressures and audience tastes informed the overall musical culture of East Germany.

The Deutsche Demokratische Republik, also known as the DDR, was originally a Soviet satellite state developed in the years after World War II in which the Soviet Union, the United States of America, and the United Kingdom were jointly supervising as the best course of action for the territory was being decided. After six years of geopolitical limbo, governing autonomy was slowly transferred to German Communist officials who quickly determined that there was immeasurable value in developing a universal system of music regulation. The SED’s urgency to manage the art of East Germany was in some ways inspired by the founder of communist ideology, Karl Marx, and how he describes the ways in which music has the capacity for being used as a tool for both unification and separation. In her paper, Celia Applegate isolates a particular quote from Marx which reinforces this by saying the following:

Still, the “present condition of nations, and more particularly of our German nation” suggested to Marx that “a new spirit of higher self-consciousness, of greater independence, of brotherly union and energetic moral energy” had been “awakened”. This spirit, he concluded “may indeed be stunned, restrained, misled, calumniated, or denied, but cannot be annihilated”. That Marx should have adopted such a determinedly internationalist tone at the end of his life suggests the difficulties of regarding even the most overtly German of music critics as someone engaged in the business either of cutting off Germany from the rest of the musical world or, even worse, asserting German musical superiority over the music of every other nation.

During the early years of the DDR, former members of the German Communist Party who had fled from the Third Reich during World War II felt compelled to return home in order to assist in the rebuilding of the nation with the intent of “denazifying” German culture and musical identity. This encouraged many discussions that revolved around the way in which orchestras could most effectively remove fascist elements from their programming and ultimately distance fledgling East Germany from the traumatic memories of the Third Reich. For example, in the years following World War II, Leipzig officials felt a strong need to salvage what they could of German culture from a time before the corrupting effects of Nazism through the identification of more politically appropriate historical figures. With that goal in mind, the SED turned to reinvigorating the works of Johannes Sebastian Bach, who was born in Eisenach and spent much of his professional life in the territory considered to be East Germany. Bach’s association with the region and strong connections to the German Lutheran traditions made him a clear choice upon which to focus their efforts. By regularly celebrating his legacy and reinforcing the importance of his contributions, government officials ultimately found themselves in a lively discourse surrounding the final resting place. City representatives argued whether or not he should be interred at either the Johanniskirche or Thomaskirche, both of which being of historical value to the composer, which brought international recognition to the DDR. Placing iconic musicians back into the fold of everyday life became a powerful device of unification as the SED attempted to curate the budding culture of East Germany. Although he was not directly associated with the DDR, Bach consequently became an important linchpin that encouraged the German people to reconnect with their identity and foster a sense of pride while sifting through the “rubble of their country”.

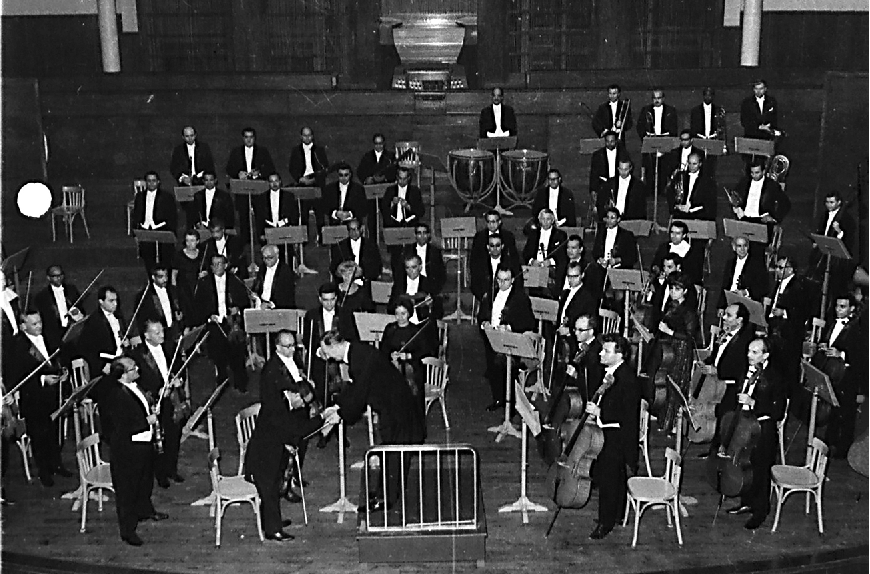

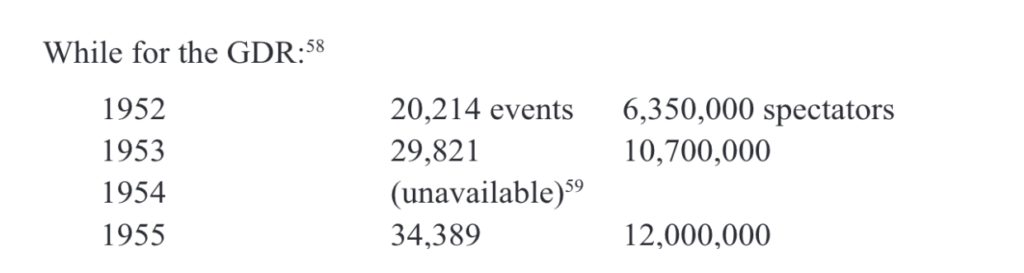

In addition to encouraging the consumption of traditional concert music by artists such as Bach, the SED was also determined to provide the public with modern works consisting of strong Marxist messages. Labeled as “socialist realism” this loosely defined set of artistic expectations imposed by the political system was built upon nostalgic qualities of music from the past yet transcended bourgeois elements that limited access to these styles. The SED was extremely motivated by socialist realism as a way to position the DDR as a superior entity to the West, both socially and culturally. This push into politically charged original compositions resulted in the need for a massive web of government-managed orchestras varying in size and degree of talent, all of whom were tasked with creating programming to entertain and educate the masses. In data collected from 1953 across the seven districts of the city of Rostock, it was shown that there were 354 successful concerts that were organized by the government which accumulated approximately 40,000 attendees. Rural and working-class areas were also capable of pulling healthy numbers from a few dozen to hundreds despite having significantly smaller ensembles to attend. In his research, Tompkins creates a more holistic picture of yearly concert attendance and its increase throughout the earlier years of the DDR which is seen in the following table:

Figure 1: Yearly attendance of classical music concerts in East Germany

According to the number of spectators, live classical music was a popular fixture in the DDR for people across socioeconomic levels, but it also showed where the citizens were beginning to express their frustrations with having entertainment controlled by the state.

Throughout the 1950s, it became clear that there were two main forces driving the development of East German music: the powerful SED and the average East German Citizen. During this time, the public regularly voiced a sense of dissatisfaction with compositions in the style of socialist realism and requested a lighter musical fare. As a result, the SED slowly felt compelled to slightly relax the rules surrounding programming by 1956 in order to allow for more diverse and appealing listening opportunities. In addition to voicing their longing for more apolitical content, East German concertgoers would often refuse to attend concerts that were not made up of a more diverse repertoire. As Silverberg mentions, “although party officials advocated a conservative, total, classicizing, musical language, the small group of composers in musicologists argued that modernist techniques had a rightful place in new socialist music”. Despite often being labeled as a totalitarian government, there was still a notable flexibility driven by the citizens of East Germany, and their desire to have a say in their own culture by communicating their experience of living on the other side of the Iron Curtain.

In an effort to continue satisfying the public, nostalgic composers from the past who were found to be less associated with toxic nationalism and consequently lauded as being particularly “progressive” were coupled with the works of living composers. The SED compromised with the ticket holders by designing a system in which the popular classics and modern socialist realism pieces could come together in one East German sound for the benefit of both taste and political education. In the DDR, carefully curated performances of Beethoven were juxtaposed with celebrations of new works by the local talents of Hans Eisler, while Ruth Berghaus attempted to redefine the classic works such as Wagnerian Operas by taking them out of the twisted framework of fascism. This tactic made it much more likely that those who attended a concert would enjoy a majority of the content, and associate the more politically driven music with an overarchingly positive experience. That being said, despite the SED’s best attempts to control the airwaves of East Germany, the people found a way to pressure the government in order to allow for music that was more to their taste.

As Tompkins points out in his book, “workers, peasants, and the traditional urban concertgoers encountered Bach and Chopin, but also cantatas about Stalin and mass songs praising the party, and performance spaces from traditional concert halls to factory clubhouses and rural venues”. The SED designed a series of programs that encouraged orchestras to connect with the working class in their space so as to disseminate not only an appreciation for art but additionally educate the public on Marxist ideologies through music. It was not lost on the SED that art was a powerful tool to communicate information to the masses, which ultimately led them to create a massive web of performance venues and many different program series, both on the radio and in towns across the country. In addition to making it geographically accessible, the SED stated that politically acceptable programs were exempt from the entertainment tax, which was an additional way to encourage the consumption of socialist material. Although the SED did have the goal of fostering a unique musical identity for the East German people, there still was a sense of tension within the community that stemmed from the ways in which some of the content performed was clearly intended as propaganda.

With their attempts to create an acceptably socialist sound for the proletariat, came Western critics using musicological benchmarks with capitalist underpinnings to evaluate the country’s developing musical aesthetic. Although similar discussions about rebuilding were also occurring in West Germany, tensions over which German cultural heritage was the true post-Nazi identity were still deeply divisive. It was a commonly-held, yet largely unfounded belief that West Germany was more prone to art on an international scale, while the East was more confined and conservative. East German composers in fact were able to travel beyond the boundaries of the DDR to places such as Darmstadt to take music courses and often were in contact with other composers from outside of their region. Additional collaborative projects in both East and West Germany were also established through institutions such as the Akademie der Künste with the intention of encouraging creativity and a connection with the outside world. Even with the limitations of travel and the negative sentiments held by the West, the DDR interacted with and consumed content from the outside world, but still chose to prioritize their original artistic content with the intent of asserting themselves as an independent nation.

Even with the small spirit of camaraderie between the two Germanies, a fundamentally unique aspect of East German music which separated itself from its Western counterparts was the desire to introspectively evaluate the successes and failings of socialism. Layered underneath political propaganda and the desire to separate themselves from the dark history of a fascist Germany, was a genuine push by artists to explore the possibility and practicality of a socialist utopia. The leftist SED successfully managed to seize the means of music production for the sake of producing content free of elitism and for the people, but yet failed to solidify a lasting impression on the world. Despite this, there still were artists continuing to explore how music had the ability to elicit a utopian image in regards to socialism, while also allowing space for contemplation of the issues that erupted from living in such an isolated state. Much of the art during the 40 years of the DDR’s existence focused on the concept that socialism was unable to solve the problems of the world, yet the alternative capitalist systems failed in their own ways to find solutions as well. Regardless of socialism’s musical representation as a complex utopian idea that desired to enact social change, there still was a distinctive underlying current of doubt and confusion throughout the East German musical community. Fighting through the pervasiveness of socialist realism and Marxist inspiration, composers in the DDR still used their music to express a sense of concern for the longevity of the nation, and the conflicting emotions around the government’s goal of creating a “socialist utopia”.

Ultimately, it can be said that the SED had a very strong hold on the overall sound being created in East Germany and that the resulting musical culture was one steeped in propaganda. It can also be said that the people of the DDR created a unique style of music that was a reflection of living in an isolated, idealistic socialist state that deeply affected the psyche of its citizens. Scholarly literature in recent history seems to have a habit of falling back on beliefs that stem from capitalist biases without looking into the other factors that inspired East German musicians to create their original art. When exploring the reasons for making music, an argument can be made that it was an outlet for the German people to recover from and reflect upon the past atrocities committed by the Third Reich, while also bringing together the tastes of both the bourgeois and proletariat classes so as to create a more unified country. Despite the fact that the SED is reported to have overseen around 200 orchestras of various sizes, it is noted that the citizens of the DDR fought on behalf of, and retained elements of musical autonomy. This in turn, developed a unique sound that combined elements of Marxist thought, modern techniques programmed with German classics, and an overarching theme of hope and uncertainty for the future of the DDR.

Bibliography

Applegate, Celia. “The Internationalism of Nationalism: Adolf Bernhard Marx and German Music in the Mid-Nineteenth Century.” Journal of Modern European History 5, no. 1 (March 2007): 139–59.

Beard, Danijela Š., and Elaine Kelly. “Introduction to the Special Issue on Music and Socialism.” Twentieth-Century Music 16, no. 1 (February 2019): 3–5.

Demshuk, Andrew. “A Mausoleum for Bach? Holy Relics and Urban Planning in Early Communist Leipzig, 1945–1950.” History and Memory 28, no. 2 (2016): 47.

Kelly, Elaine, and Amy Wlodarski, eds. “Art Outside the Lines: New Perspectives on GDR Art Culture. German Monitor”, no. 74. Amsterdam ; New York: Rodopi, 2011.

Kelly, Elaine. “Art as Utopia: Parsifal and the East German Left.” The Opera Quarterly 30, no. 2–3 (September 1, 2014): 246–66.

Kelly, Elaine. Composing the Canon in the German Democratic Republic: Narratives of Nineteenth-Century Music. Oxford University Press, 2014.

Silverberg, Laura. “Between Dissonance and Dissidence: Socialist Modernism in the German Democratic Republic.” Journal of Musicology 26, no. 1 (January 1, 2009): 44–84.

Sprigge, Martha. Socialist Laments: Musical Mourning in the German Democratic Republic. New Cultural History of Music Series. New York: Oxford University Press, 2021.

Thacker, Toby. Music After Hitler, 1945–1955. 1st ed. Routledge, 2017.

Tompkins, David G. Composing the Party Line: Music and Politics in Early Cold War Poland and East Germany. Central European Studies Series. West Lafayette, Indiana: Purdue University Press, 2013.